Road to recovery: Cancer in the COVID-19 era

As COVID-19 continues to disrupt Canada’s cancer system, attention needs to be given to three key focus areas to boost system capacity and save lives

Road to recovery: Cancer in the COVID-19 era

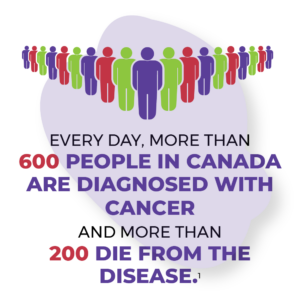

Every day, more than 600 people in Canada are diagnosed with cancer and more than 200 die from the disease.1 This was the reality before COVID-19 disrupted health care for patients and providers alike. While the entire health system is struggling with the consequences of the pandemic, cancer must remain a top priority: its tendency to spread in the body means the later people are screened and diagnosed, the greater the risk that lives will be lost unnecessarily.

Every day, more than 600 people in Canada are diagnosed with cancer and more than 200 die from the disease.1 This was the reality before COVID-19 disrupted health care for patients and providers alike. While the entire health system is struggling with the consequences of the pandemic, cancer must remain a top priority: its tendency to spread in the body means the later people are screened and diagnosed, the greater the risk that lives will be lost unnecessarily.

With cancer, time is of the essence

COVID-19 caused disruptions across the entire health system, including the cancellation or postponement of clinical exams and procedures — leading to many cancers going undiagnosed or untreated. The longer a cancer goes undetected, the worse the outcomes are likely to be: a more advanced stage at diagnosis, poorer survival rates, and greater disease- and treatment-related issues. The effect of these delays and the rising backlog of undiagnosed cases is magnified for populations that have been underserved – differences in access to resources, power and privilege have all contributed to health inequities for these populations that have been further exacerbated by the pandemic.

COVID-19 caused disruptions across the entire health system, including the cancellation or postponement of clinical exams and procedures — leading to many cancers going undiagnosed or untreated. The longer a cancer goes undetected, the worse the outcomes are likely to be: a more advanced stage at diagnosis, poorer survival rates, and greater disease- and treatment-related issues. The effect of these delays and the rising backlog of undiagnosed cases is magnified for populations that have been underserved – differences in access to resources, power and privilege have all contributed to health inequities for these populations that have been further exacerbated by the pandemic.

Because the burden of disease and the magnitude of avoidable deaths is greater than other conditions,2 cancer must be prioritized when allocating healthcare resources as Canada continues to deal with the impacts of the pandemic. While efforts to build more resilience into the cancer system, increase access to prevention, screening and treatment, and deliver services in more efficient and innovative ways are all underway, there is much more to be done.

To improve care and outcomes for cancer patients, health equity must be at the forefront of Canada’s pandemic response and recovery. In addition, three key areas will require increased attention from policymakers and cancer system players alike:

Burnout and attrition among cancer care providers and other health human resources, especially nurses, therapists and technicians, are affecting the ability of the cancer system to meet current needs.

Disruptions in prevention, early diagnosis and treatment services may lead to a surge in cases diagnosed at later stages as well as delayed care needs in the months and years to come — and the system will need more capacity to respond optimally.

New models of care, supported by digital tools, will help address system capacity and access constraints, but they require investments and changes to care policies and processes.

Expecting a surge

An estimated two in five people in Canada will be diagnosed with cancer in their lifetime: around 229,000 people every year.1 A higher than normal number of new cancer diagnoses is anticipated over the next couple of years due to pandemic-related screening delays, suspensions of elective cancer-detecting procedures such as biopsies and scopes, travel disruptions that prevented people from seeing healthcare providers, and patients’ reluctance to see their primary care providers in person.

The impact of these delays could be stark: observational studies have shown that treatment delays by even four weeks can be associated with as much as 6-13% increased risk of death.3 The latest research already shows that the longer wait times associated with the slowdowns of cancer surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic are projected to lead to decreased long-term survival for many patients with cancer.4

For some populations that already faced considerable delays before the pandemic as well as other inequities in cancer prevention due to systemic barriers within the healthcare system, their situation has only been worsened by COVID-19. For example, people who live in lower income neighbourhoods are more likely to experience diagnostic delays following an abnormal breast or colorectal cancer screening test.5 In addition, First Nations people living on a reserve in Ontario may be more likely to experience delays following an abnormal screening test.5

Learn what could happen without cancer system capacity to handle the surge.

A system under strain

Canada already lags behind other developed countries in its cancer system capacity, falling below the OECD average in numbers of practising physicians and key diagnostic resources such as MRI and CT scanners.6 Canada also has the longest wait times for specialist services.7 The pandemic has made those shortcomings even more pronounced.

This matters because cancer touches every part of the health system — and requires a much larger footprint of healthcare workers to deliver everything from pre-operative assessments to surgeries, chemotherapy and more. So as healthcare resources were reassigned and redeployed to manage COVID-19 cases, the cancer system faced challenges on multiple fronts that still need to be addressed.

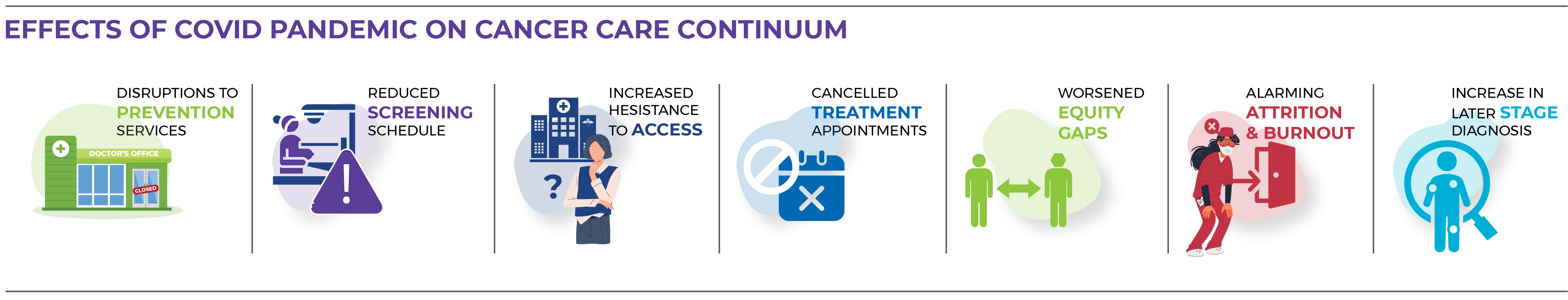

- There have been disruptions to cancer prevention services, notably human papillomavirus (HPV) immunization programs for school aged children, but also evidence of increases in the prevalence of behavioral risk factors, such as alcohol use, during the last two years.8,9,10

- People have generally not received screening on the same schedules or with the same frequency as before the pandemic. This may lead to more cancers going undiagnosed and untreated, or being diagnosed at a later stage and resulting in poorer outcomes.

The routine mammogram that diagnosed my breast cancer was delayed by seven months because of COVID-19.

Cancer patient11

- Some patients have not seen their healthcare providers in person for more than two years, which is problematic given that many cancers require hands-on assessment to accurately diagnose. Some populations, including First Nations, Inuit and Métis, have also felt more hesitant to access healthcare services during the pandemic due to past experiences with systemic racism.12

- Many patients have had cancer treatment appointments cancelled and some have even had surgeries postponed, creating a growing backlog that will likely take years to address if new strategies are not implemented.

- Attrition and burnout remain a top concern among clinical care providers — and job vacancies in the health sector are growing at an alarming rate.

Learn more about the current state of Canada’s cancer system.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis are disproportionately affected

The strength and resilience of First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities have generated innovative ways to keep community members safe during the pandemic while ensuring their healthcare needs are met. But the impacts of colonialism and other determinants of health (such as lack of clean water, overcrowding, food insecurity, poverty, limited access to health care and systemic racism) have produced health inequities that the pandemic exacerbated. Those inequities continue to have a disproportionate impact on the health and well-being of First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

The strength and resilience of First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities have generated innovative ways to keep community members safe during the pandemic while ensuring their healthcare needs are met. But the impacts of colonialism and other determinants of health (such as lack of clean water, overcrowding, food insecurity, poverty, limited access to health care and systemic racism) have produced health inequities that the pandemic exacerbated. Those inequities continue to have a disproportionate impact on the health and well-being of First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

Read about the ways First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities have responded to the pandemic.

Populations that have been underserved face worsening health inequities

For populations that have been underserved, differences in access to resources, power and privilege have contributed to health inequities worsened by the pandemic. Populations that have historically experienced health and social inequities, such as racialized, lower-income and recent immigrant communities, are more likely to contract COVID-19 — often because they are precariously employed in low-paying jobs that do not allow them to work from home.13 These populations are also more likely to experience obstacles to getting the care they need, including cancer care.

For populations that have been underserved, differences in access to resources, power and privilege have contributed to health inequities worsened by the pandemic. Populations that have historically experienced health and social inequities, such as racialized, lower-income and recent immigrant communities, are more likely to contract COVID-19 — often because they are precariously employed in low-paying jobs that do not allow them to work from home.13 These populations are also more likely to experience obstacles to getting the care they need, including cancer care.

Find out how COVID-19 has affected people with cancer who experience inequities.

Focused attention is needed now

How can we work together to make the cancer workforce more resilient, increase system capacity and bring innovation to the delivery of cancer services? How do we ensure that a post-pandemic cancer system puts equity at the forefront? What mix of system and policy changes supported by practical on-the-ground tactics and new models of care can prepare the cancer system to meet the coming surge in demand of new cancer patients, and patients with more advanced cancers — and ensure cancer doesn’t fall behind as other parts of the healthcare system also look to tackle similar challenges?

How can we work together to make the cancer workforce more resilient, increase system capacity and bring innovation to the delivery of cancer services? How do we ensure that a post-pandemic cancer system puts equity at the forefront? What mix of system and policy changes supported by practical on-the-ground tactics and new models of care can prepare the cancer system to meet the coming surge in demand of new cancer patients, and patients with more advanced cancers — and ensure cancer doesn’t fall behind as other parts of the healthcare system also look to tackle similar challenges?

Read about the actions needed and innovative solutions that can help strengthen the cancer system.

This web page is a growing, evolving resource and will be updated over time to incorporate new data and address additional aspects of the cancer system.

- Canadian Cancer Society. Cancer statistics at a glance. Available from: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics/cancer-statistics-at-a-glance

- Lang JJ, Alam S, Cahill LE, Drucker AM, Gotay C, Kayibanda JF, et al. Global Burden of Disease Study trends for Canada from 1990 to 2016. CMAJ. 2018; 190(44):e1296-1304.

- Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, Jalink M, Paulin GA, Harvey-Jones E, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020; 371:m4087.

- Parmar A, Eskander A, Sander B, Irish JC, Chan KKW. Impact of cancer surgery slowdowns on patient survival during the COVID-19 pandemic: a microsimulation modelling study. CMAJ. 2022; 194(11):e408-14.

- Walker MJ, Meggetto O, Gao J, Espino-Hernandez G, Jembere N, Bravo CA, et al. Measuring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on organized cancer screening and diagnostic follow-up care in Ontario, Canada: A provincial, population-based study. Prev Med. 2021; 151:106586.

- OECD. Cancer care: Assuring quality to improve survival. 2013. OECD Publishing. Available from: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/cancer-care_9789264181052-en

- Commonwealth Fund. 2016 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Adults. 2016. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2016/nov/2016-commonwealth-fund-international-health-policy-survey-adults

- Diamond L, Clarfield L, Forte M. Vaccinations against human papillomavirus missed because of COVID-19 may lead to a rise in preventable cervical cancer. CMAJ. 2021; 193:e1467.

- Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction. 25% of Canadians (aged 35-54) are drinking more while at home due to COVID-19 pandemic; cite lack of regular schedule, stress and boredom as main factors. 2020. Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-04/CCSA-NANOS-Alcohol-Consumption-During-COVID-19-Report-2020-en.pdf

- Thompson K, Dutton DJ, MacNabb K, Liu T, Blades S, Asbridge M. Changes in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring gender differences and the role of emotional distress. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2021;41(9):254-63.

- Canadian Cancer Society patient engagement survey. January 2022. Data available upon request.

- Mashford-Pringle A, Skura C, Stutz S, Yohathasan T. What we heard: Indigenous Peoples and COVID-19: Supplementary report for the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada’s report on the state of public health in Canada. 2021. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19/indigenous-peoples-covid-19-report/cpho-wwh-report-en.pdf

- Nana-Sinkam P, Kraschnewski J, Sacco R, Chavez J, Fouad M, Gal T, et al. Health disparities and equity in the era of COVID-19. J Clin Transl Sci. 2021; 5(1):e99.