Model of Care Toolkit

Network models

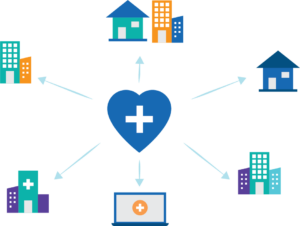

In the healthcare system, a network model is a group of specialized services that are delivered and coordinated at one centre and is connected to multiple other centres for treatment delivery and support.

In the healthcare system, a network model is a group of specialized services that are delivered and coordinated at one centre and is connected to multiple other centres for treatment delivery and support.

Evidence shows that network models:

- Improve the time from referral to initial assessment

- Reduce wait-times for accessing specialized services in tertiary centres

- Improve patient outcomes and survival rates.3,4

- Allow patients to remain with their families, caregivers, and support systems

- Enhance access to culturally appropriate care, especially for First Nations, Inuit and Métis patients

- Reduce out of pocket costs for patients and reduce overall cost of care across the health system.5,6

Organized by region, networks support access to specialist care closer to home. Patient care plans can be developed with specialists in collaboration with providers at community cancer centres rather than relying on patients travelling long distances to receive care. Understanding when a patient needs to visit their oncologist is an important part of the network model. The routine collection and use of Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO) helps trigger the transfer of a patient from a community cancer centre to a tertiary centre. The network model puts the patient at the centre of the care.

In countries like Canada, where population density varies significantly across regions, network models improve access to care in rural and remote communities. It allows for relatively seamless integration of community centres into these networks and ensures continuity of care in rural and remote regions.

Network models also have the potential to greatly improve continuity of care and enhance timely access to specialized services for First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Care for First Nations, Inuit and Métis is often complicated by a lack of coordination among hospitals, provincial and territorial health systems, cancer programs and a patient’s home community.

While network models add capacity to ensure more integrated cancer services in all settings, these models also require multi-level governance processes that are responsive to the strengths and limitations of specific jurisdictional cancer programs.

Change management considerations must include input from all levels of a cancer system and include consultation with community health centres to ensure a holistic approach is developed.7

The Ottawa Health Services Network Inc (OHSNI) is a unique inter-jurisdictional network that connects care teams in Nunavut and Ottawa to streamline care delivery for patients living in Nunavut.

The Ottawa Health Services Network Inc (OHSNI) is a unique inter-jurisdictional network that connects care teams in Nunavut and Ottawa to streamline care delivery for patients living in Nunavut.

- Practitioners in Nunavut send patient referrals and current medical records to the OHSNI case management team in Iqaluit.

- Referrals are sent to relevant practitioner(s) in Ottawa and appointments are scheduled in consultation with the patient and northern practitioner. When possible, appointments are scheduled together to minimize a patient’s time away from home.

- The patient, who may be accompanied by an escort and/or an OHSNI interpreter, travels to Ottawa to receive care.

- Upon arrival, OHSNI arranges services in English or Inuktitut and walks the patient and their escort through what to expect. Details like travel to and from appointments, who will be at the appointments and the goals of each appointment are covered to ensure the patient is fully informed and comfortable with the process.

- After the appointments are completed and the patient returns home, the case manager calls the patient to discuss next steps and answer any follow up questions a patient may have.

A key success of OHSNI is the comprehensive approach to coordinated care. With OHSNI serving as the communication hub, practitioners can share treatment and medical records and collaborate on treatment decision making. The patient-centric approach to care reduces treatment delays and contributes to a seamless patient experience.

OHSNI also runs in-person and virtual specialty clinics in Nunavut, provides education and training to enhance cultural competency among Ottawa Hospital practitioners, and participates in research activities to further collective understanding of the health care needs of northern populations.

In response to recruitment challenges of general practitioners to support community cancer clinics, Alberta developed an innovative virtual care model that maximizes the role of specialized oncology nurse practitioners in a tertiary cancer centre and registered nurses working in the community.

The model works as follows:

- The specialized oncology nurse practitioners hold virtual weekly clinics with patients in community cancer centres.

- These nurse practitioners are in turn supported by medical oncologists who coach the nurses in optimal care practices while supporting their ongoing competency development.

- Community-based registered nurses attend the virtual visits and provide on-site support to patients, working with the nurse practitioners to facilitate assessments.

- In some instances, community-based registered nurses lead visits with patients who do not need assessments by nurse practitioners each cycle.

To support best available care, the tertiary centre-based nurse practitioners are available to the registered nurses at the community site throughout the week to guide and address care needs as they arise.

Connect with Alberta’s model lead.

Quebec’s cancer networks organize care and service delivery around specialized and subspecialized interprofessional teams at multiple centres. These disease site-specific networks create clear and defined links between individuals within the care team and teams at different centres. The model has been fully implemented in lung cancer and is being expanded to other disease sites.

For patients, centralizing specialized services in small centres improves access to expertise in rural and remote areas and timeliness of access to services. The program’s “quick access desk” streamlines the diagnosis and treatment planning process and reduces costs associated with unnecessary testing or duplication of diagnostic services.8

For team members, the network promotes knowledge sharing across sites leading to improved standardized protocols and homogenous practice. The team-based approach helps reduce isolation of the staff and develop the resilience of individuals and organizations.

- Andermann A. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):E474-E483.

- Riley-Behringer M, Davis MM, Werner JJ, Fagnan LJ, Stange KC. The evolving collaborative relationship between Practice-based Research Networks (PBRNs) and clinical and translational science awardees (CTSAs). J Clin Transl Sci. 2017;1(5):301-309.

- Stone CJL, Vaid HM, Selvam R, Ashworth A, Robinson A, Digby GC. Multidisciplinary clinics in lung cancer care: A systematic review. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(4):323-330.e3.

- Brown BB, Patel C, McInnes E, Mays N, Young J, Haines M. The effectiveness of clinical networks in improving quality of care and patient outcomes: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1).

- Hunter RM, Davie C, Rudd A, et al. Impact on clinical and cost outcomes of a centralized approach to acute stroke care in London: A comparative effectiveness before and after model. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70420.

- Reeders J, Ashoka Menon V, Mani A, George M. Clinical profiles and survival outcomes of patients with well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors at a health network in new South Wales, Australia: Retrospective study. JMIR Cancer. 2019;5(2):e12849.

- Tremblay D, Touati N, Roberge D, et al. Understanding cancer networks better to implement them more effectively: a mixed methods multi-case study. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):39.

- Labbe C, Martel S, Fournier B, Saint-Pierre C. P1.15-13 wait times for diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer across the province of Quebec, Canada. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(10):S615-S616.

- Sedgewick JR, Ali A, Badea A, Carr T, Groot G. Service providers’ perceptions of support needs for Indigenous cancer patients in Saskatchewan: a needs assessment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021;21(1)