Beginning the journey into the spirit world

Indigenous perspectives on palliative and end-of-life care

The rights of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and the commitment to full partnerships and relationships are articulated in Section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982).1 Furthermore, this section of the Constitution Act reflects a promise on the part of the Government of Canada and associated entities to respect the distinct rights of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples as well as the treaty obligations that create a framework for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and non-Indigenous People to work and live together.

In 2007 and 2015, two notable Indigenous declarations and reports were published that informed discussions and corresponding actions in Canada and internationally with regards to Indigenous rights, well-being, engagement and partnerships.

![]()

“As healthcare providers, we have a responsibility to emphasize personhood and dignity in the face of illness, to be with people and hear their stories, and to provide not just physical care for the body, but mental, spiritual and emotional care for the mind, heart and spirit.”

-Alexander Kmet, Métis physician specializing in Anaesthesia, GP Oncology and Palliative Care Medicine in Whitehorse, Yukon

The wrinkles around her eyes curled to highlight the uncontainable joy of her grin as she mimed shooting a moose one more time. An Elder, from a First Nation community outside of Whitehorse, emphasized the importance of returning home from the hospital into the care of her community, knowing that her advanced cancer would progress without ongoing medical treatment. As a palliative care physician living in the Yukon, I have witnessed firsthand the importance of honouring culture, tradition and connection to both community and the land during the end-of-life journey.

As healthcare providers, we have a responsibility to emphasize personhood and dignity in the face of illness, to be with people and hear their stories, and to provide not just physical care for the body, but mental, spiritual and emotional care for the mind, heart and spirit. This is especially true when caring for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, for whom history and experiences are inextricably linked to health and well-being.

Regardless of your experience or role in palliative care, Beginning the journey into the spirit world: First Nations, Inuit and Métis approaches to palliative and end-of-life care in Canada provides insights and teachings that will support you and others in your caregiving journey.

-Alexander Kmet, Métis physician

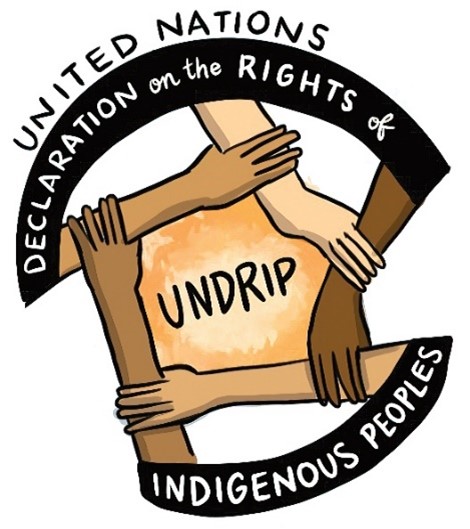

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

UNDRIP was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on September 13, 2007 and by Canada in 2016. This declaration establishes a comprehensive international framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the Indigenous Peoples of the world. It elaborates on existing human rights standards and fundamental freedoms as they apply to the specific situation of Indigenous Peoples.

UNDRIP was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on September 13, 2007 and by Canada in 2016. This declaration establishes a comprehensive international framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the Indigenous Peoples of the world. It elaborates on existing human rights standards and fundamental freedoms as they apply to the specific situation of Indigenous Peoples.

The following are notable UNDRIP articles that relate to Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care:

Article 7: Indigenous individuals have the rights to life, physical and mental integrity, liberty, and security of person. 2

Article 21: Indigenous peoples have the right, without discrimination, to the improvement of their economic and social conditions, including inter alia, in the areas of education, employment, vocational training and retraining, housing, sanitation, health and social security.3

Article 23: Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for exercising their right to development. In particular, Indigenous peoples have the right to be actively involved in developing and determining health, housing and other economic and social programmes affecting them and, as far as possible, to administer such programmes through their own institutions.4

Article 24: Indigenous individuals have an equal right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. States shall take the necessary steps with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of this right.5

For more information, watch How UNDRIP Changes Canada’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Calls to Action

From 2008 to 2014, the TRC heard stories of abuse (for example, mental, emotional, sexual, physical) from thousands of residential school survivors. The purpose of the TRC was to document the history and impacts of the residential school system in Canada. The TRC provided former residential school survivors with an opportunity to share their experiences during public and private meetings held across Canada. In June 2015, the Commission released a report based on these hearings, resulting in 94 calls to action. The TRC calls to action address the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation.

The following are TRC calls to action that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada specifically asked the Partnership and our colleagues in health institutions across the country to realize:

The following are TRC calls to action that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada specifically asked the Partnership and our colleagues in health institutions across the country to realize:

TRC call to action #22. We call upon those who can effect change within the Canadian health-care system to recognize the value of Aboriginal healing practices and use them in the treatment of Aboriginal patients in collaboration with Aboriginal healers and Elders where requested by Aboriginal patients.6

TRC call to action #23. We call upon all levels of government to:

-

- Increase the number of Aboriginal professionals working in the health-care field

- Ensure the retention of Aboriginal health-care providers in Aboriginal communities

- Provide cultural competency training for all health-care professionals7

TRC call to action #24. We call upon medical and nursing schools in Canada to require all students to take a course dealing with Aboriginal health issues, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, and Indigenous teachings and practices. This will require skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism.8

Reconciliation is not about forgiving and forgetting. Rather, reconciliation is about remembering and changing.

Furthermore, reconciliation is not a final destination: it is a shared journey and process for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and non-Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

As people living and working in Canada, we all have individual and collective roles in advancing the TRC calls to action.

For more information about the TRC final report, refer to Honouring the Truth, Reconciliation for the Future

UNDRIP and the TRC calls to action shine a light on the importance of understanding the historical, social, cultural and political landscape that shape relationships between Indigenous Peoples and institutions such as the health-care system in Canada. Understanding this landscape and these relationships is crucial to achieving social justice. As orders of governments, health-care organizations, and related leadership and education groups implement the TRC calls to action and the UNDRIP articles, helpers need to be aware of their roles when working with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples living with life-limiting illnesses, their families and communities.

- Recognize the effects of historical and intergenerational trauma on Indigenous Peoples—These effects are often associated with the policies of forced assimilation through the residential school system and other forms of colonization in Canada (for example, Indian Act legislation and the reserve system, land appropriation, Indian hospitals,9 Sixties Scoop.10)

- Deconstruct one’s understanding of change at the community level—First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities set the pace and define (or redefine) ways of knowing related to identity/identities; resiliency; palliative and end-of-life care. It is important to recognize that a community’s readiness to engage in or lead Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care will differ within and between First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities.

- Engage communities—Take the time needed to grow relationships and sustain trust among individuals, groups and organizations who provide Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care and related support to individuals with life-limiting illnesses.

- Understand processes and protocols for working with and alongside First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities—Understanding these processes and protocols includes acknowledging, recognizing and understanding cultural practices associated with dying and death.

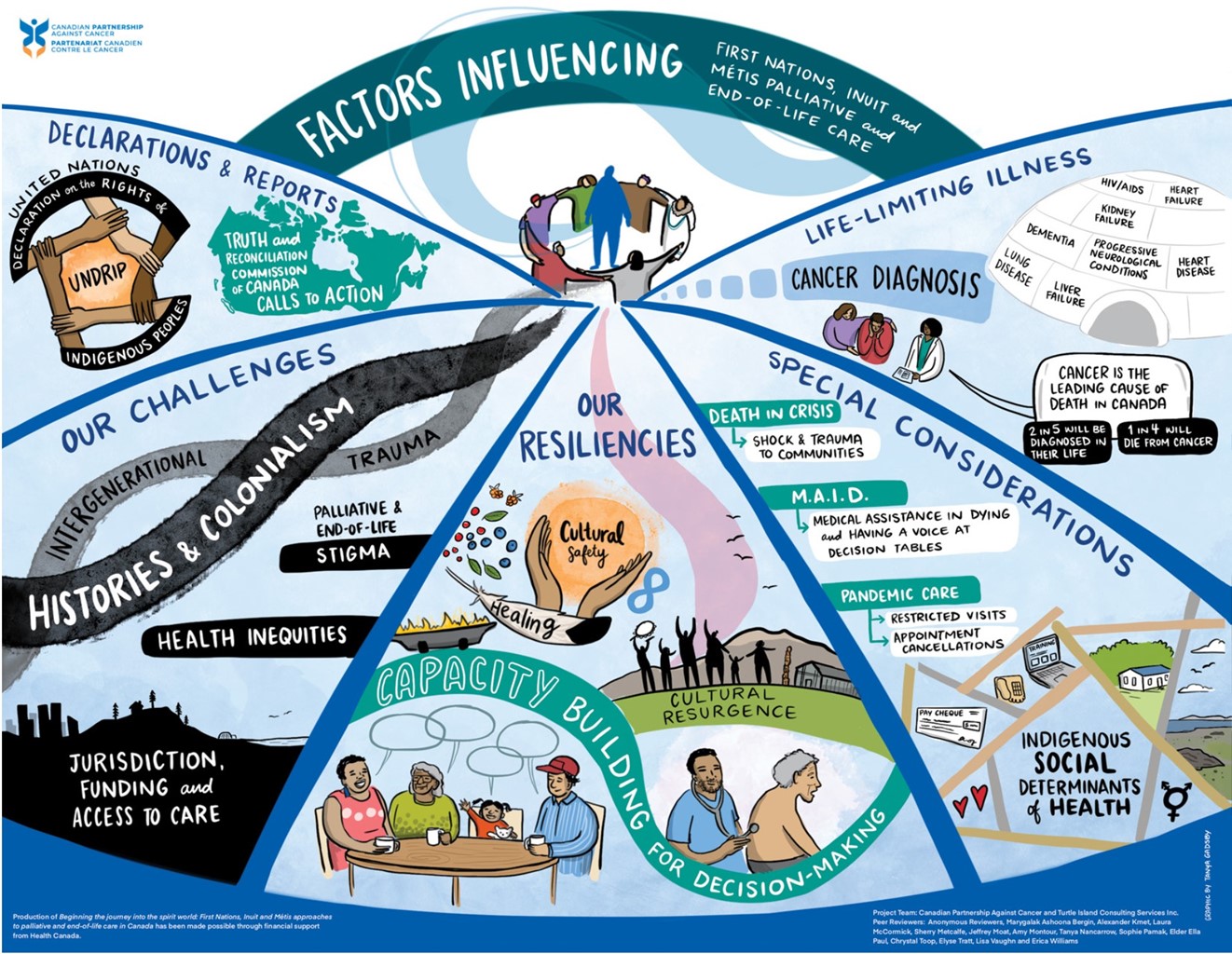

Challenges and resiliencies

Many First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, their families and communities may look at palliative and end-of-life care from worldviews that differ from non-Indigenous Peoples and biomedical perspectives. Many factors impact and influence palliative and end-of-life care for Indigenous Peoples.11,12,13 Some of these factors are historical factors, jurisdictional factors, cross-cultural factors, capacity building factors and resource factors.

Historical factors

When we reflect on the history of Canada, it is important to view it as a living history in terms of past and current effects of colonization, the residential school system and associated intergenerational implications as reflected in current health care, the legal/justice system and child welfare policies and practices. History did not start with colonial history: Indigenous cultures survived and thrived in what is now called Canada for millennia. Indigenous communities in Canada had a profound relationship with the land which supported livelihoods and spiritual and cultural well-being.14 However, historical dispossession of lands in Canada occurred through colonial wars and/or formal treaties;15 the creation and implementation of Indian Act legislation and the reserve system;16 depopulation by epidemics of European diseases (for example, smallpox, influenza, measles);17 and unilateral appropriation of Indigenous lands, territories and resources.18,19,20,21

The historical context of harm resulting from colonization continues to affect Indigenous Peoples across the generations. This harm is often called intergenerational trauma. These historical factors influence health decisions that include Indigenous Peoples living with life-limiting illnesses being able to access palliative and end-of-life care programs, services and resources.22,23

The residential school system and the enduring legacies of intergenerational trauma are major factors impacting and influencing Indigenous health, healing and helping. Colonialism creates an oppressive environment whereby Indigenous Peoples are unable or not allowed to express anger and frustration because it is too dangerous or risky. Feelings of alienation and marginalization can turn inward and be directed at oneself and/or one’s families and communities.

There are often feelings of fear and apprehension in accessing palliative care, especially for Indigenous Peoples and their family members who were forcibly removed from their communities, languages and ways of life as part of the residential school system, Indian hospital system and/or the Sixties Scoop. Their fears and apprehensions center on questions such as, Will there be any options in palliative care? Will I be forced to leave my family, community, language and way of life to enter into a biomedical health care setting for palliative care? Will my palliative care choices and decisions actually be heard, respected and supported in the health-care system?

Access to palliative and end-of-life care—jurisdiction and funding

Access to palliative and end-of-life care is based on health-care jurisdiction and funding as part of intergovernmental relations. The Government of Canada (federal order of government) has responsibility for Indigenous Peoples, while the delivery of health-care services in Canada is primarily a provincial/territorial responsibility. In Canada, palliative and end-of-life care are typically hospital-based and provincially/ territorially-organized.

Jurisdiction (law making authority) creates added complexities for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples attempting to access care. Health inequities also exist between First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and communities. While the Indian Act limits the health-care rights for (Status/registered) First Nations Peoples, Métis Peoples and Inuit are typically not afforded the same rights to health care as First Nations Peoples.24,25 Lack of cultural support and services for urban Indigenous homeless populations means that they are not likely to receive any kind of Indigenous-specific palliative and end-of-life care. Also, in many Inuit regions and communities in Canada, there are little to no palliative and end-of-life care services.26,27,28

Jurisdiction (law making authority) creates added complexities for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples attempting to access care. Health inequities also exist between First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and communities. While the Indian Act limits the health-care rights for (Status/registered) First Nations Peoples, Métis Peoples and Inuit are typically not afforded the same rights to health care as First Nations Peoples.24,25 Lack of cultural support and services for urban Indigenous homeless populations means that they are not likely to receive any kind of Indigenous-specific palliative and end-of-life care. Also, in many Inuit regions and communities in Canada, there are little to no palliative and end-of-life care services.26,27,28

Coupled with problems arising from jurisdiction is the inadequate availability of sustainable funding support for Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care which is driven by policies, government mandates (priorities) and laws/regulations.29 The failure to address social determinants of health for Indigenous Peoples in urban, rural, remote and northern communities,30 as well as the exclusive use of a biomedical (non-holistic) approach to health care can disempower many Indigenous families and communities and erode their confidence to provide palliative and end-of-life care and engage in traditional healing practices for family members living with life-limiting illnesses.31 Institutional health-care policies and protocols have posed and continue to pose barriers to traditional practices and cultural grieving processes due to the restrictions on number of visitors, length of visit and the practice of traditional ceremonies, particularly ceremonies for dying and death. These restrictions challenge the valued Indigenous traditions of being surrounded by the entire family and using traditional practices such as preparing special foods, engaging in pipe ceremonies and smudging.32 Also, access to medications, supplies and home care are not equitable in many rural, remote and northern communities.

Engagement, partnership and capacity building

With growing recognition of Indigenous title and rights in Canada, there is a need to promote Indigenous models of self-determination with a focus on the negotiation of practical and workable arrangements to implement self-government with jurisdiction and funding associated with health care (including palliative and end-of-life care). To enhance meaningful engagement in authentic intergovernmental relations, all orders of government must actively participate in the form of partnerships and collaborations. They must work alongside Indigenous Peoples with life-limiting illnesses, their families, communities and health-care providers to enhance capacity for palliative and end-of-life care through self-government, self-determination and sustainable community development.

With growing recognition of Indigenous title and rights in Canada, there is a need to promote Indigenous models of self-determination with a focus on the negotiation of practical and workable arrangements to implement self-government with jurisdiction and funding associated with health care (including palliative and end-of-life care). To enhance meaningful engagement in authentic intergovernmental relations, all orders of government must actively participate in the form of partnerships and collaborations. They must work alongside Indigenous Peoples with life-limiting illnesses, their families, communities and health-care providers to enhance capacity for palliative and end-of-life care through self-government, self-determination and sustainable community development.

In 2018, Maamwesying North Shore Community Health Services and the SE Health First Nations, Inuit and Métis Program partnered to develop a natural caregiver education and training program. This program’s purpose is to provide natural caregivers (community-based caregivers and family members) with practical skills-based training that supports their helping roles.33

Maamwesying North Shore Community Health Services and the Saint Elizabeth Health First Nations, Inuit and Métis Program implemented the natural caregiver education and training program in three phases:

Phase one: Coordinating dialogue sessions to create culturally safer space for natural caregivers to share stories and experiences that could then inform learning priorities, support needs and other related considerations (for example, gaps, challenges, hopes, aspirations and promising practices).

Phase two: Delivering natural caregiver training based on priority needs identified in phase one of the program.

Phase three: Expanding the development of prepared curricula that address identified needs from phase one and informed by the delivery of training education in phase two. This phase also included advancing a train-the-trainer component to support community-based health care providers with sustained natural caregiver education.34

Natural caregiver education and training focuses on traditional teachings, practices and medicines; illnesses and conditions; medication support; palliative care; and self-care. Training sessions are experiential and interactive and involve scenarios, case studies, energizers and collaborative learning.35

Nothing about us without us

This statement signifies that local engagement and consultation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and communities is required when developing and implementing palliative and end-of-life care programs.

Community engagement and partnerships in palliative and end-of-life care involve organizations and orders of government (for example, Indigenous governments/communities, provincial/territorial governments and the federal government). They include Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care in the form of supports and services that are multidisciplinary and expand across sectors (health, justice, skills development and employment and social services–to name a few).

Community engagement has been recognized as a cornerstone of primary health care for at least thirty years (WHO, 1978), and continues to be promoted in current debates on social and Indigenous determinants of health as a key to addressing health inequities.36,37

Community engagement and partnerships encourage First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities and organizations to work cooperatively with health-care initiatives, policies, protocols and quality improvement to ensure a holistic continuum of health services, resources and supports that are timely, accessible and culturally congruent for Indigenous Peoples, their families and communities.

Capacity building involves developing knowledge, skills and abilities to empower Indigenous Peoples to participate in any or all aspects of decision-making in their communities, regions, provinces/territories and the country as a whole. Capacity building also includes program planning, development, implementation and evaluation intended to enhance holistic palliative and end-of-life care.

For some Indigenous communities, capacity building has been hampered by many challenges, in particular socio-economic barriers (for example, high unemployment rates, low labour force representation, low wage earners, inadequate housing and overcrowding).38,39,40 Despite these barriers, many Indigenous communities have broadened and continue to broaden the scope of capacity building and availability by acknowledging that the answers are in the community. They honour and recognize the strengths, existing roles and capabilities of families and communities, for example, Elders, Knowledge Carriers, Indigenous healers and helpers, community leaders, families and friends. These family and community members are an extended collaborative network of healing and helping support and resources for people living with life-limiting illnesses.41,42

For some Indigenous communities, capacity building has been hampered by many challenges, in particular socio-economic barriers (for example, high unemployment rates, low labour force representation, low wage earners, inadequate housing and overcrowding).38,39,40 Despite these barriers, many Indigenous communities have broadened and continue to broaden the scope of capacity building and availability by acknowledging that the answers are in the community. They honour and recognize the strengths, existing roles and capabilities of families and communities, for example, Elders, Knowledge Carriers, Indigenous healers and helpers, community leaders, families and friends. These family and community members are an extended collaborative network of healing and helping support and resources for people living with life-limiting illnesses.41,42

Indigenous resilience and cultural resurgence

Indigenous resilience and cultural resurgence are empowering many Indigenous Peoples to reclaim their First Nations, Inuit or Métis identities. Examples of empowerment are connecting or reconnecting to land, people, place and Indigenous spirituality.43 Cultural resurgence also includes revitalization of traditional livelihoods, Indigenous languages and community engagement. This resurgence is facilitating opportunities for many Indigenous Peoples to connect or reconnect with their Indigenous identities as sources of resiliency for enhancing self-esteem in the form of renewing purpose and vision in their lives.

Indigenous resilience and cultural resurgence draw on core values and resiliency factors that transcend First Nations, Inuit and Métis worldviews. Examples of values and factors are collectivism and interconnectedness—the relationship between land, identity, people and place and roles of families and communities;

Indigenous resilience and cultural resurgence draw on core values and resiliency factors that transcend First Nations, Inuit and Métis worldviews. Examples of values and factors are collectivism and interconnectedness—the relationship between land, identity, people and place and roles of families and communities;

balance/harmony between mind, body, spirit and emotions; Aboriginal title and inherent rights (land decisions) and self-determination.44,45,46,47 However, diversity among Indigenous Peoples and communities in languages, lifestyles and teachings means there is no singular “one size fits all” worldview held by all Indigenous Peoples across Canada.

Indigenous healing, helping and cultural safety

Based on the ground-breaking work of Elaine Papps, Irihapeti Ramsden and Māori experiences in the health-care system,48 cultural safety (kawa whakaruruhau) is defined as “an outcome based on respectful engagement that recognizes and strives to address power imbalances inherent in the system. It results in an environment free of racism and discrimination, where people feel safe.”49 Furthermore, “cultural safety is based on a framework of two or more cultures interacting in a colonized space – where one culture is legitimized and the other is marginalized. This can happen in hospitals, schools, workplace[s], and in many different service settings.”50

Culturally safer practices are actions in colonized spaces (for example, biomedical health-care settings) where First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, their families and communities feel respected, included, welcomed and comfortable being themselves and expressing all aspects of who they are as Indigenous Peoples.

Culturally safer practices are actions in colonized spaces (for example, biomedical health-care settings) where First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, their families and communities feel respected, included, welcomed and comfortable being themselves and expressing all aspects of who they are as Indigenous Peoples.

1. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/principles-principes.html

2. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf (p. 6).

3. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf (p. 9).

4. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf (p. 9).

5. Ibid.

6. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wpcontent/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf (p. 3).

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. As part of the Government of Canada’s assimilation policy, the government created segregated Indian hospitals. Indigenous Peoples were sent to under-resourced Indian hospitals from residential schools, northern Canada and northern parts of the prairie provinces. Medical experiments (for example, forced sterilization, forced confinement for tuberculosis treatment) were carried out at the Charles Camsell Hospital. Currently, there is litigation on injustices that occurred at Indian hospitals; https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/a-brief-look-at-indian-hospitals-in-canada-0.

10. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sixties_scoop/ and https://www.sixtiesscoopsettlement.info/.

11. Caxaj CS, Schill K, Janke R. Priorities and challenges for a palliative approach to care for rural Indigenous populations: a scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2018;26(3):e329—e336.

12. http://www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/55/4/394.full.pdf

13. Lemchuk-Favel L. The provision of palliative end-of-life care services in First Nations and Inuit communities. FAV COM; 2016, January.

14. Nelson M, Natcher DC, Hickey CG. Subsistence harvesting and the cultural sustainability of the Little Red River Cree Nation In: David D, editor. Seeing beyond the trees. The social dimensions of Aboriginal forest management. Concord (ON): Captus Press; 2008. p. 29–40.

15. Weaver JC. The great land rush and the making of the modern world, 1650–1900. Montreal (QC): McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2003.

16. First passed in 1876, the Indian Act gave the Government of Canada exclusive authority over those First Nations communities who were recognized as “Indians” living on reserves which were unilaterally created; https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1536350959665/1539959903708.

17. Tennant P. Aboriginal peoples and politics: the Indian land question in British Columbia, 1849-1989. Vancouver (BC): UBC Press; 1999.

18. Bhandar B. Status as property: identity, land and the disposessions of First Nations women in Canada. Dark Matter. 2016;14:1–20.

19. https://www2.unbc.ca/sites/default/files/sections/neil-hanlon/2009_hanlon_dialoguesfinalreport.pdf

20. DeCourtney CA, Branch PK, Morgan KM. Gathering information to develop palliative care programs for Alaska’s Aboriginal Peoples. Journal of Palliative Care. 2010;26(1):22–31.

21. Harris C. Making native space: colonialism, resistance, and reserves in British Columbia. Vancouver (BC): UBC Press. 2002.

22. Macaulay AC. Improving Aboriginal health: how can health care professionals contribute? Canadian Family Physician. 2009, April;55:334–336.

23. de Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, Greenwood, M. Rethinking (once again) determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ health. In: Greenwood M, de Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, editors. Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ health: beyond the social. 2nd ed. Toronto (ON): Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2018.

24. Jacklin K, Warry W. Decolonizing First Nations health. In: Kulig JC, Williams AM, editors. Health in rural Canada. Vancouver (BC): UBC Press; 2012. p. 374–375.

25. Krieg B. Bridging the gap: accessing health care in remote Métis communities. In: Kulig JC, Williams AM, editors. Health in rural Canada. Vancouver (BC): UBC Press; 2012.

26. Lavoie JG, Gervais L. Access to primary health care in rural and remote Aboriginal communities: progress, challenges, and policy directions. In: Kulig JC, Williams AM, editors. Health in rural Canada. Vancouver (BC): UBC Press; 2012.

27. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. First Nations cancer control in Canada baseline report. Toronto (ON); 2013.

28. Kaufert JM, Wiebe R, Lavallée M, Kaufert PA. Seeking physical, cultural, ethical, and spiritual “safe space” for a good death: The experience of Indigenous Peoples in accessing hospice care. In:Coward H, Stajduhar KI, editors. Religious understandings of a good death in hospice palliative care. Albany State: University of New York Press; 2012. p. 231-256.

29. Anderson M, Woticky G. The end of life is an auspicious opportunity for healing: decolonizing death and dying for urban Indigenous People. International Journal of Indigenous Health 2018;13(2):48–60.

30. O’Brien V. Person-centered palliative care: a First Nations perspective [thesis]. Hamilton (ON): McMaster University; 2012.

31. Giesbrecht M, Crooks VA, Castleden H, Schuurman N, Skinner M, Williams A. Palliating inside the lines: the effects of borders and boundaries on palliative care in rural Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;168:273–282.

32. Habjan S, Prince H, Kelley ML. Caregiving for Elders in First Nations communities: social system perspective on barriers and challenges. Canadian Journal of Aging. 2012;31(2):209–222.

33. Kelly L, Linkewich B, Cromarthy H, St. Pierre-Hansen N, Antone I, Gilles C. Palliative care of First Nations people: a qualitative study of bereaved family members. Canadian Family Physicians. 2009;55(4):394–395.

34. SE Health First Nations, Inuit and Métis Program. Caregiver education partnership final report: Maamwesying, North Shore Community Health Services. 2020.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Lavoie JG, Gervais L. Access to primary health care in rural and remote Aboriginal communities: progress, challenges, and policy directions. In: Kulig JC, Williams AM, editors. Health in rural Canada. Vancouver (BC): UBC Press; 2012.

38. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. First Nations cancer control in Canada baseline report. Toronto (ON); 2014.

39. Kaufert JM, Wiebe R, Lavallée M, Kaufert PA. Seeking physical, cultural, ethical, and spiritual “safe space” for a good death: the experience of Indigenous Peoples in accessing hospice care. In: Coward H, Stajduhar KI, editors. Religious understandings of a good death in hospice palliative care. Albany State: University of New York Press; 2012. p. 231–256.

40. Kelley ML, Prince H. Recommendations to improve quality and access to end-of-life care in First Nations communities: policy implications from the “improving end-of-life care in First Nations communities” research project. Thunder Bay (ON): Lakehead University; 2014.

41. Hordyk SR, Macdonald ME, Brassard P. End-of-life care in Nunavik, Quebec: Inuit experiences, current realities, and ways forward. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2017;20(6):647–655.

42. Kelley ML, Prince H. Recommendations to improve quality and access to end-of-life care in First Nations communities: policy implications from the “improving end-of-life care in First Nations communities” research project. Thunder Bay (ON): Lakehead University; 2014.

43. Brant Castellano M. Updating Aboriginal traditions of knowledge. In: Sefa Dei G, Rosenberg B, editors. Indigenous knowledges in global contexts: multiple reading of our world. Toronto (ON): University of Toronto Press; 2000.

44. Absolon K, Willet C. Putting ourselves forward: location in Aboriginal research. In: Brown L, Strega S, editors. Research as resistance: critical, Indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches. Canadian Scholar’s Press; 2005.

45. Brant Castellano M. Updating Aboriginal traditions of knowledge. In: Sefa Dei G, Rosenberg B, editors. Indigenous knowledges in global contexts: multiple reading of our world. University of Toronto Press; 2000.

46. Hart MA. Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and research: the development of an Indigenous research paradigm. Journal of Indigenous Voices in Social Work. 2010;1(1):1–16.

47. Simpson L. Anishinaabe ways of knowing. In: Oakes, J, Riew R, Koolage S, Simpson L, Schuster N, editors. Aboriginal health, identity and resources. Native Studies Press; 2000. p. 165-185.

48. Papps E, Ramsden I. Cultural safety in nursing: the New Zealand experience. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 1996;8(5):491–497.

49. https://www.fnha.ca/what-we-do/cultural-safety-and-humility

50. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/family-and-social-supports/child-care/ics_resource_guide.pdf